Dong Ha to Dong Hoi: 212 Miles

Whilst I was waiting for bike parts in Da Nang, another typhoon was brewing in the South China Sea, determined to spoil my fun.

I could wait it out, but was now under some time pressure. I had plans with my Dad and needed to be in Hanoi within a week.

With all the delays getting the bike fixed, I’d need bit of help anyway, so bought a train ticket to Dong Ha, just up the coast. This saved two days’ ride and bought me an important head start on the storm.

From Dong Ha, my first stop was Khe Sanh; site of a disastrous siege for the US during the war. The stuff of Springsteen lyrics, Khe Sanh became a symbol of US failures and seemed to evoke a moment in time and general feeling as much as a place. It felt weird to be riding my bike there.

Weighed down by history, perhaps; today Khe Sanh is a pretty ordinary border town, and for me, in true Central Highlands style, it lay 60km away, up a big hill. I cycled slowly, looking for a good breakfast stop to propel me up the climb .

In the end, I was flagged down by a curious bunch, nursing some hefty caphe phin and jossing with the customers at the adjoining banh mi stand.

Hai (pictured below), was keen to make sure I was looked after.

Having studied in Europe under an exchange scheme in 80s, he said he understood foreigners and was glad of the company. We talked for a good hour.

As for everyone in Vietnam, history was real for Hai; his adolescence a traumatic time for the country, with millions in the south ‘re-educated’, whilst others fled by boat.

Still, there were reasons to be optimistic when he left for East Germany in 1987. On the surface, Vietnam was part of a huge socialist power bloc, still officially promising a future utopia for all prepared to contribute. Being shipped off to Europe from small town Vietnam, perhaps this seemed plausible.

Hai reminisced about a lover from Poland, driving holidays they took around Belarus and Czechoslovakia, his host family, but most of all, he was fond and proud of his time studying as a structural engineer.

When he returned in 1994, everything had changed. There were no jobs, he said, and he’d been forced to spend the bulk of his working life as a truck driver, never making use of his qualifications.

I sensed his disappointment, but to me it still seemed an extraordinary experience.

“Yes”, he agreed, reluctantly, “but the ghost is now heavy and sad”.

“I want to return”, he sighed, “and burn incense for my host family, but for now it’s impossible”.

Jaded by the false promises of the past, Hai worried about me out on the road: “buy what you need here”, he warned, “elsewhere they will overcharge you. It’s not like it was”.

He recommended I take some lotus bean cake, apparently the stuff of legend. “Travellers have carried it for centuries”, he swore, “if you can’t find a hotel, if you’ve nowhere to stay, eat some lotus bean cake!”.

Loaded up with my mythical supplies, I hit the road, and after a few hours reached Khe Sanh town, where I paused before pressing on a little further to the old US base, now site of a small museum.

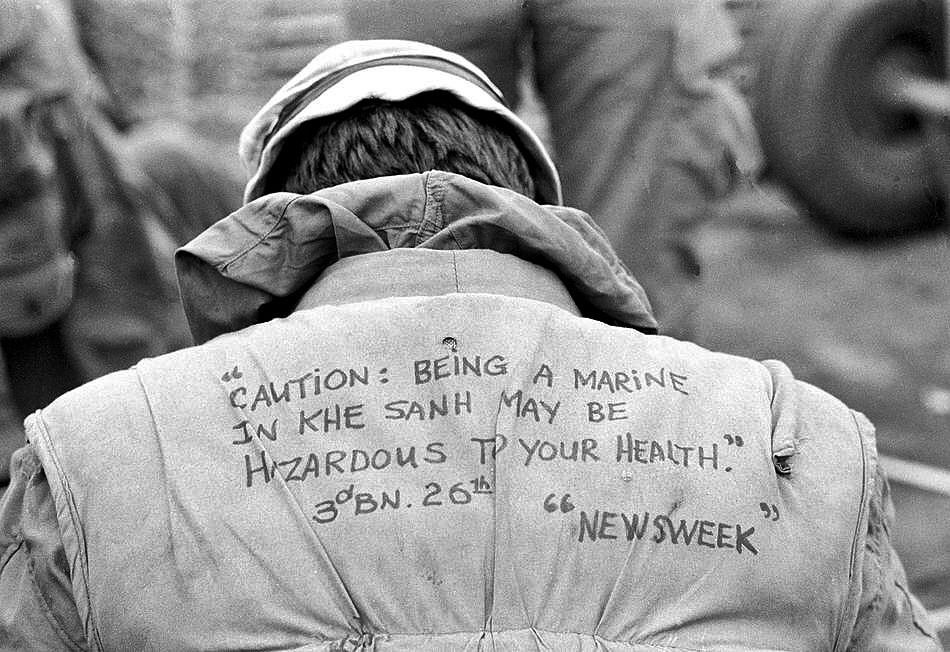

Here, in January 1968, 6,000 US marines found themselves besieged, surrounded by 20,000 VC, under heavy bombardment and reliant on airdrops for survival. With intense media interest, the US command ordered the base to be defended ‘at all costs’, Johnson even had a scale model of the battlefield made up in the Oval Office. Today by contrast, the site is quiet, announced only by a small, faded and easily missed sign, just off the HCM road.

I followed it and parked my bike – a powerful silence looming over the airfield. A couple of young American girls were up on a private tour from Hue. They took a photo on the steps, whilst an older Vietnamese couple made their way solemnly through the small exhibition. Aside from these visitors, the once bloody and chaotic base stood empty and still.

For local people things have moved on and the area now has a growing reputation for its excellent coffee.

But a rusting B52 sums up the atmosphere on site. As Hai said earlier, ‘heavy and sad’ – especially when flicking through the guestbook which tells of vets and their families making the emotional return trip. I couldn’t read the Vietnamese comments, for the north though, suffering and casualties were even worse.

After chatting to Hai and seeing the base, my ride felt somewhat trivial, though after some miles, perhaps more important too – a rare freedom in a world still short of it.

Beyond Khe Sanh lay the most remote section of the Ho Chi Minh Road: 240km, one motel, 3 petrol stations and just one or two shops.

I knew it was considered an adventurous route for motorbike tourers, but only managed to find two reports from people that had actually cycled it: a pair of Bristol Uni graduates who’d found nowhere to stay and ran out of biscuits, and an American who’d had a torrid time in non-stop rain.

Part encouraged (part rattled), I gave some big business to the donut vendor in Khe Sanh town.

Then rested at a basic motel down the road where the staff prepared me this enormous carb fest to eat in the corridor outside my room.

I needed it. The next day’s riding was tough, it felt cold and windy and the hills were big. The hard days are o

Up on the tops I saw almost nobody and, as I reached for my jacket in the wind, began to worry that I’d miscalculated the path of the typhoon. Down in the valleys though, the weather was calm and I passed some interesting wooden hamlets.

Even out here the usual charming kids were out in force to count my gears and cheer me on.

There were occasional road crews too; hard living mountain folks camped out under tarpaulin. There is next to nothing in terms of commercial traffic on this route – yet a lot of effort to keep it in top condition.

Most men have an instinctive desire to squeeze the bike tires. The road crews, in their camo and pith helmets, went one further, squeezing my legs and thighs too, before roaring with laughter when I told them where I was off to!

Passing through a small village in a valley, a group of teenage girls appeared, arranging themselves quickly in a neat line, ready for high-fives. ‘More encouragement’, I thought with a smile, only for each in turn to give me the “TOO SLOW!” treatment, as exaggeratedly as they could before (rightly) falling about in hysterics at my expense.

There was certainly a sense of humour up here.

Aside from these brief encounters, I did my best to keep moving and ended up riding 108km and 1700m of ascent without as much as a sit down. The mysterious lotus bean cake was doing its job.

After many hours in the saddle I finally arrived at Lon Son where I hoped to stay in the motel – the only one on this 240km stretch. It looked like it had gone out of business, but the door was open so I figured I could at least sleep on the floor.

It turned out it was just very minimal on furniture, guests and staff. Eventually someone appeared.

Evening set in and I went for a wander around. Villagers lit incense at family alters, workers returned from the fields and a couple of young boys approached to proudly show me their collection of Pokemon and DragonBall-Z cards.

In the morning, these same kids looked tiny as they made their way purposefully across the dramatic valley on their way to school.

There weren’t any restaurants as such in Lan Son, but I’d managed to arrange for a neighbour of the motel to make me a packed lunch of banh mi baguettes. Still, looking at the gradient profile, I was a bit worried about running out of food and decided to make a detour around the 20km mark to a promising looking ‘knife and fork’ symbol, down a dead end road on Google Maps.

Here I found a very enterprising lady who, having cornered the market, was very happy to stop what she was doing and cook me a big bowl of noodles at several times the normal cost. In fact, she wanted to cook me an entire chicken at first! When I paid, she gave me an armful of snacks produced from the backs of various drawers around the house, in lieu of change. With another 80km to go to the next stop, this worked out pretty well.

As I climbed, the scenery went up notch with the road now slicing right through some beautiful sections of pristine forest.

I saw two or three motorbikes, but nothing else for the next two hours. In this emptiness the bike felt increasingly small and vulnerable; a wooden row boat in an ocean of towering trees and slopes.

Clouds set in on the top and a man appeared, ghost like in the distance. He was barefoot, his clothes ripped and his hair long and matted. He was full day’s walk from anywhere. I wanted to offer him some food and water, but in the vast emptiness, felt a bit spooked and rode right by. I hope he was ok.

After two days’ climbing, a long, but quick descent took me abruptly out of the wilderness and straight into the backpacker enclave of Phong-Nha.

Phong-Nha is famous for its absurdly big caves and I spent a day exploring these and the incredible surrounding scenery in the rain before retreating to the Western comforts of the hostel.

From here it was a short ride the next day to Dong Hoi train station on the coast where I’d head up to Hanoi.

After 4 months alone, I was off to meet my Dad 🙂