Ha Tien to Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon): 275 miles

I feel bad for saying so, but after Cambodia, arriving in Vietnam was a bit of a relief.

Food options were abundant, the use of Roman script gave me a fighting chance and after all the dirt roads and dust, everything just felt so cheerful and clean.

Kids go home for lunch and when I passed a school (a few hundred metres from the border), nearly everyone said (or shouted!) hello, motorcyclists waved the Vs (peace sign) and even the elderly, to this point – totally inscrutable, occasionally made a point of greeting me too.

In addition to such welcoming people, Vietnam also has its own unique aesthetic…

The kids’ track jackets, for instance, were often brand new, but the design from a different era

Vintage style helmets were the norm – like for this guy, trying on my glasses

Pastel colours had preference

And whilst conical hats remain a practical choice for those at work…

…John Lennon spec’s and bright red lipstick rule in the cities

I felt like I was in a new place.

Though Vietnam is still nominally communist, I was a bit surprised to see quite so many propaganda posters and even more surprised to hear crackly loudspeakers continuing to broadcast party news and patriotic songs across the countryside. Both seemed like quaint relics rather than anything oppressive or Orwellian.

…That’s what they want you to think, at any rate!

Vietnam only opened up to the world in the 1990s and the party machine hasn’t gone away.

Across the country, Uncle Ho takes on the role of benevolent grandfather. Giant images outside schools picture him reading to kids whilst the ruthless General Giap (architect of the Viet Minh victory at Dien Bien Phu), smiles benignly, like a kind neighbour, over busy intersections.

Aside from defeating both the French and the Americans, the Party’s most lasting triumph is perhaps that over history itself, with strong restrictions in place around any discussion of the war or Party activity, continued bans on ‘culturally poisonous’ literature and harsh treatment of dissidents and human rights activists in what is still a one party state.

Despite the above, a romantic image of the war prevails. ‘Harmless’ propaganda posters have become popular souvenirs, whilst the guerilla-nostalgia themed ‘Cong Caphe’ (a stylish coffee chain in which you are served by staff dressed as VC – yes, this is real!) is now expanding internationally.

I’d only just arrived. So, after beginning to process some of the above, finding an ATM and registering for a SIM card (photo and passport please, comrade), it was time to sit down for a coffee.

This is what arrived:

Many have made their fortune rattling off pithy lines about why we travel. Perhaps this sums it up better than anything though –being utterly baffled by something so universal and familiar! Fabulous 🙂

A national obsession, coffee is cheap, strong, fresh and available everywhere. Pictured is the traditional Caphe Phin – in more serious places (like the above) this is served still brewing, allowing you the pleasure of decanting over ice yourself. Be careful though, you’re dealing with liquid uranium! Playing it safe, many add almost equal quantities of condensed milk. Sensible, but insufficient. As such it is usually served with tea as a chaser, sometimes a whole pot! “Tea or coffee?” is a question which doesn’t need asking.

As you can tell, I quite enjoyed this coffee and sat a good while, taking in my first views of the Mekong Delta. So much so, I lost track of time, realising in a panic at 2.00pm that I still had around 90km to go to Rach Gia, the nearest significant town.

At other points in the trip I could afford to be a bit more blasé, but the good people of the communist party require foreigners to register their passports at their accommodation each night – even when staying with a friend. This meant it might be trickier to ask locals to put me up. In theory they would need to contact the police and ask permission first.

90km it was then, and with a storm closing in, the race was on.

For motivation, I decided to play ‘Speed’ – my version of Keanu Reeves’ 1994 classic, reimagined for the bicycle. If I kept the speedometer above 20km p/h, I’d make it to town not long after dark, if I didn’t, the bomb would go off! I surprised myself at how hard I rode, but unfortunately, there were several explosions:

- There was a heavy rainstorm (I don’t think Keanu Reeves had to deal with one of those)

- Vietnamese bus drivers are totally wild. They have silly horns but take no prisoners – I had to pull in on narrow sections.

- A couple of hours in, all traffic stopped dead and a huge crowd appeared in the middle of the road.

Souped up on my plutonium coffee and still musing on the party apparatus, I assumed this was some kind of political demonstration (the kind the FCO encourage you to avoid).

Great. Not only was I late, I was also about to get tear gassed.

The baton charge was slow in arriving, so I cautiously edged a little nearer.

This was not a demo – it was the school run! How embarrassing…

Kids seemed to be going to or from school incessantly in Vietnam, so I came across plenty of scenes like this at kick out time – sometimes (like in the picture) the kids act as their own lollipop lady/man and hold up traffic with a rope. After a while, someone somewhere blows a whistle, the kids drop the rope and run, and the ensuing scrum is like some kind of Black Friday rush, by motorbike.

With all the interruptions/explosions I ended up cycling in the dark way longer than I would have liked. Roadside weddings and karaoke provided the soundtrack as I made my way through clouds of steaming pho and smokey BBQ from a procession of evening vendors. The lights from these places provided just enough of a glow for me to navigate the potholes on the last 20km. It wasn’t cool. But it was pretty cool.

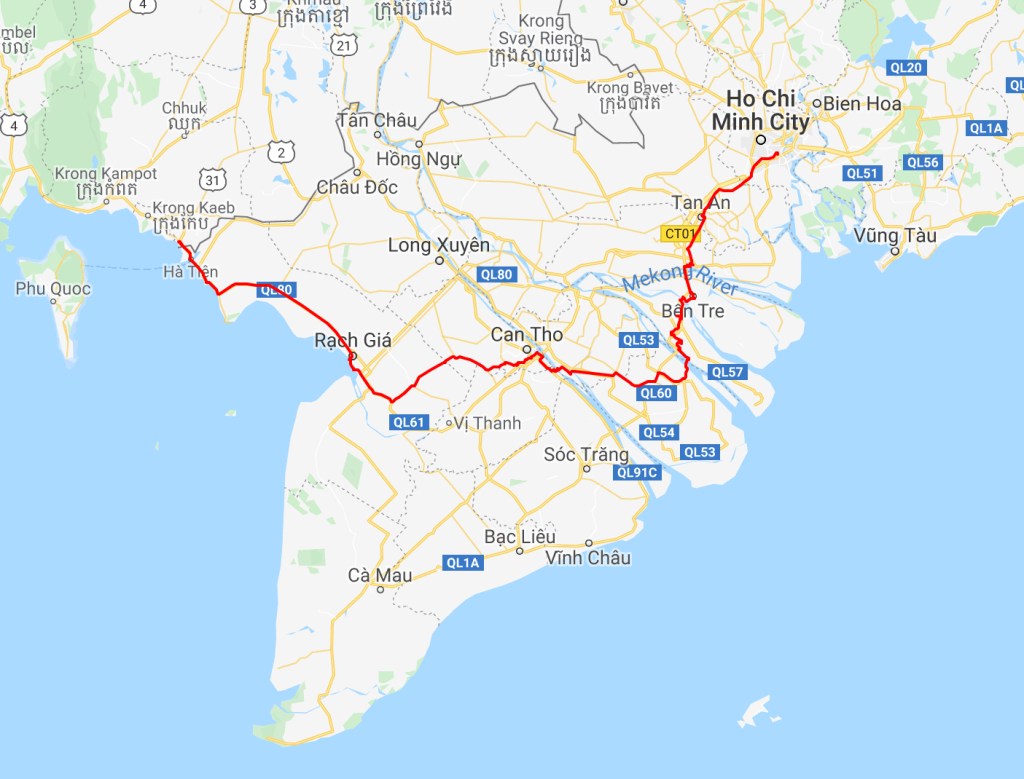

My real goal was the Mekong which, after snaking its way through six countries, takes a bow in south Vietnam before splitting off like a firework into the complex labyrinthine of canals, tributaries and islands that makeup its vast delta – Vietnam’s most productive region. So dense are the waterways, that during the war, far more in the way of materiel and supplies was smuggled south by sea (through the Delta) than ever was by land through the more famous (and much romanticised) HCM trail. My plan was to pick my way across the Delta right through to Saigon, using creaky bridges, local ferries and small access roads where possible.

My first day proper on the Delta was busy and peaceful at the same time.

School kids – again – were everywhere (maybe they go home for morning break too?), so I had plenty of deep and repeated conversations about my name, age and “where are you from?”. I really liked these kids. In a lot of countries I’ve cycled I might get an ironic ‘hello’, followed by a private giggle at the moron foreigner. I expect this. Vietnamese kids were different though, they laughed openly, but rarely at me. Many were super helpful with their parents’ businesses and would pause TV / homework to help communicate – they seemed genuinely curious.

**Later, in both HCM and Hanoi, I actually had kids come up to me (their parents supervising from a distance), just to say ‘Hello, can I speak some English with you for a few minutes?’. One girl told me she would like to go to English club (“like my sister”), but can’t for now, so instead comes with her mum to a tourist spot for an hour or two each weekend, just to shoot the breeze with whoever might be around. (She was 11!)**

Amazing little people require at least moderately amazing adults, so let me talk about the Vietnamese that flagged me down from time to time. I’m talking here about street vendors. I don’t know what spell these guys cast on me, but (even though I was a paying customer), in the countryside I often felt I was being flagged down as a new friend. Much fuss was made over getting me a seat, getting me in the shade, and generally getting me as comfortable as possible for the interrogation that followed. My route was usually of marginal interest, filler; much more important was my marital status (followed by immediate suggestions of potential wives in the vicinity), my job and, of course, my gigantic salary.

This innocent looking lot were one such group of interrogators.

I was enjoying a 7up with them when a lady wandered over selling some lethal looking fried shrimpy things – no thank you kind lady – haven’t you been reading my blog? I’m allergic!

“How about one of these?”, she gestured, pointing to some kind of fried ball.

“What is it?”

“Omelette”, said Google Translate.

Fair enough, bit weird though, she gave it me with a lime, a bunch of herbs and a massive pile of salt. It’s an omelette, I thought, not a tequila slammer. The first bite was quite chewy and pretty dense, a weird omelette indeed. I looked up. Everyone was staring at me, smiling expectantly like a bunch of kids in on a secret. “Dip it in the salt”, they suggested.

What was going on?

I looked again at the ‘omelette’. It was riddled with veins and worse. Google had let me down, this was not an ‘omelette’ but the infamous ‘embryo egg’ – a partially developed baby bird, incubated for a set period, then boiled alive as a local delicacy. I was eating a deep fried one. I looked again at the crowd, more smiles, “dip it in the salt…take a bite on the herbs”, they encouraged. I tried my best to protest and get out of it, “this is very unusual in my country”, I said, using the translate app. “Yes!”, they smiled, “and very healthy too!”. They were really ‘egging’ me on, so I just had to get on with it and be grateful I still had a bit of 7up left. What was I saying earlier about why we travel…?

I guess the scenery partly made up for it…

…And by the time I was hungry again I’d built up enough trust to stop – carefully – at another set of vendors at a crossroads kind of market.

I spotted a sign for Banh Mi, the famous (and in London, quite trendy), Vietnamese baguette sandwich. Here was familiar territory I thought. Not quite! Somehow I’d ordered Banh Mi’s closely related drunken cousin (no idea of the name). The lady spread the baguette with butter on all sides, barbecued it, snipped it up, threw in some herbs, then laced it with all kinds of chilli and mayo, before chucking in a big handful of quails eggs (non-embryo), peanuts, crispy garlic and onions. The ‘sandwich’ was then served with chopsticks.

It must have been a heavy night on the Saigon Beer the morning this beast was conceived. I had two whilst settling in for another friendly interview from the bunch below. Apparently I could marry the sandwich maker, if I wished, though she wasn’t around when it was discussed!

I didn’t know it at the time but I was only a few miles from Vietnam’s 4th largest city and centre of commerce for the Delta, Can Tho (*I thought I was heading for a small town).

This was a jackpot day to arrive in a big city as Vietnam were due to play Indonesia in a crucial World Cup qualifier. I asked at the hostel for a good place to watch, “come with us!”, the guy in charge said. And after a lightening quick shower I was on the back of a motorbike, heading down the breezy boulevards of Can Tho to watch the game with the hostel manager and another guest (a German-Vietnamese man). ‘What a free-spirited guy I am’, I thought, for all of around 3 seconds. Then I started to worry about who the designated driver was, and what the most polite excuse might be to turn down a return lift from these kind, (but ultimately reckless and irresponsible) people that had invited me out.

Sorry Vietnam. I underestimated you!

In all we probably passed thousands of people watching the game in pavement cafes (it’s a big city) – precisely NONE of these people were drinking beer! Did I mention their coffee is strong? I guess it’s enough. Not everyone has to lose it when their national team plays.

Now I could relax. Well, I couldn’t quite relax because the German-Viet guy was being a little strange. He’d done a few odd things and now (rather than watch on the big screen) he’d set up a tripod with his mobile phone to stream the game privately for himself. The hostel owner quietly apologised, “I don’t know him very well”, he whispered.

Well… in the middle of this important game, watched by thousands of beerless drinkers across Can Tho, the screen and lights cut out, the crowd jeered and the streets around the café plunged into darkness – a city wide blackout. The ‘weirdo’, streaming by mobile, now became the hero, waving his tripod/selfie stick in the air, updating everyone on events (including a goal), until the power came back on.

Aside from big business and blackouts, Can Tho is also famous for its floating markets: a giant wholesale one and a smaller semi-retail one, 15km down the river at Phong Dien. Until recently, much of the delta was actually quite isolated, big distances were routinely covered by boat and markets like these were the only way to shift produce. A major bridge building project has changed all that, bringing even the sleepiest backwaters within easy reach of the highway. Lorries have replaced boats, in many places, and it’s thought the current crop of floating market traders might be the last.

I asked the hostel guy for some advice about which market to visit: “don’t bother with Phong Dien”, he said, “it’s miles away, and just a handful of boats these days. A waste of time.”

Sounded great! I set my alarm for 5am and took a white knuckle Grab bike half an hour or so down the road to check it out. We got to the town but I didn’t really know where the market was and nor did the driver so I began to question my decision. Not for long though, the wonderful man below soon came sprinting up from the river and, for not much money, arranged to take me around the market in his boat, rowing and singing folk songs to himself all the while in the soft glow of early morning. (It’s a hard life this endurance bike ride business!)

After saying bye to the boatman I then checked out the much busier non-floating market – a hellish place to be an animal, but otherwise very atmospheric.

Then on to the main wholesale market where entire boat loads of produce were being unloaded and sold – the main event for most visitors.

By 9.00am I’d been up for 4 hours, seen 3 markets and eaten an entire pineapple. I then bumped into the eccentric Viet-German. I went for breakfast with him (the delicious noodle dish below) and listened intently, sat on the smallest stool imaginable, as he told me about his plans to break into the world of yacht building.

“Do you know anything about building yachts?”

“Not really. Just that I want to build them.”

Fair play.

Fuelled up, I set course for Tra Vinh, on what was a big day of ferries, islands and cane juice. The roads were sometimes narrow, even single track, but busy nonetheless, as they sliced through plantations and criss-crossed canals over rickety bridges.

I was quite late arriving and, any other day, would have been happy to collapse in an exhausted heap. Tra Vinh though, (like other Delta towns), was energising and full of life in the evenings. It was a weeknight but there were so many people out, so many coffee shops and so many smoothie venues; all unbranded, mostly unnamed and all totally unpretentious plastic chair set ups. You can hang for hours in these places with a 50p coffee, the atmosphere is pretty inclusive (not totally male) and you can show up in a giant group or alone – however you like your coffee! Great culture.

From Tra Vinh I had just one final day on the Delta – this turned out to be the headline act with stunning scenery right through.

There were more rickety bridges…

…and more ferry crossings. This one to an island in the river.

The pair below scrutinised my bike closely on the way, pinching and poking with great scepticism. It was pretty good, they finally agreed. They liked the speedometer, just a shame about the motor!

(At least I had some company)

Once on the island I spent a fun 10km or so bumping along dirt roads, to the bemusement of all that passed (no motor!?). I had a good ten minute chat with one lady about “how old are you?” (we didn’t have enough language for much else, but nobody was in a rush).

Then a sweet little girl came tearing out of her garden on a big bike with a basket to give me a more thorough inquisition. I gave her a photo, taken with the Polaroid. Then her Dad appeared wielding a snake.

“Is that your lunch?”, I joked

“Yes.”

I must have misunderstood. “Is it for E-A-T-I-N-G?” I tried again, exaggeratedly.

“Yes” (I just told you!), “for EATING”, he smiled.

From catching snakes to harvesting coconuts, everyone was working hard. At the time, this looked like a lot.

Really I’d seen nothing! The truck above was on its way to the wharf where the crop would be sorted and processed before being stacked so high into the waiting barges it’s hard to think how anyone could navigate them.

Nothing was wasted and mounds of coconut fibre, ready for processing were common along the sides of the narrow paths I took.

I really didn’t know what was around each corner, from fabulous motorbike bridges like this…

To mountains of dragon fruit…

And even an ice cream man! Of course I had one, though was gently reprimanded by an elderly lady who stepped out of her house to point out that I was eating mine in the SUN, when I could be in the SHADE.

That just the beginning of my Vietnamese grandmothering as that night I stayed in the Mama Yang homestay (in My Tho). Mama Yang, who must have been in her 70s, helped me clean my bike (there was no need!), plied me with fruit and humoured me by looking through hundreds of photos on my phone – which she almost dropped when she got to the one of the snake! ‘Apparently he was going to have it for lunch‘, I told her.

From Mama Yang’s it was a short half day to HCM/Saigon, but traffic was dense and for much of the last 5km all I could do was edge forward, inches at a time – a tube station crush on wheels.

I woke early every day in HCM. Partly to enjoy the hypnotising effects of morning Tai Chi as I walked through the parks, mostly though to hit the historic sites before anyone else.

Having taught the Vietnam War (‘American War’ if you’re in Vietnam), there was lots to keep me busy.

I spent around 4 hours in the Reunification Palace, an incredible Asian-modernist structure, and base of Thieu’s increasingly powerless RVN (South Vietnamese) government during the war.

Here is his office

And here is where he’d meet VIP visitors, like Kissinger, who showed up to pressure concessions out of the South in the run up to the Paris Peace Talks as reelection for Nixon loomed in ’72

Upstairs things were more Austin Powers than world statesman, with a private cinema, games room and helipad

The bunker reminded me of ‘The Lives of Others’ (a film about the Stasi), and is where a lot of the high level operations of the war were carried out in the Nixon era

The War Remnants Museum (another 3 or 4 hours) mentions nothing negative (at all) about the north, but gives a pretty fair write up of US escalation. There is a giant gallery dedicated to photographers (of all nationalities) that died in the conflict, and their work – very moving.

I also took a public bus out to Cu Chi – site of a well preserved tunnel complex used by the VC (and also earlier by the Viet Minh against the French). I told the guide I was a history teacher, hoping he might take it slow and give me some extra info and stories. In the end he was just very insistent that I saw (and crawled) through all of the tunnels that I could. Although they have been widened for visitors, the tunnels are still incredibly tight, cramped and full of bats. ‘They eat mosquitoes, not people’, he said, each time I protested about going further.

Whatever you think of the war, the endurance and determination of those who carried on for what became large portions of their lives at places like Cu Chi, is pretty astonishing.

Maybe even more surprising is the unbelievably welcoming attitude to Americans and Westerners alike, just decades later. People were happy to meet me wherever I went and I looked forward to hitting the road north.