Poipet to Kampot and the Vietnam Border: 460 miles

Before I got to Cambodia, a colleague got in touch with some advice: “Beautiful country, lovely people”, he said, “but make sure you do some research on the border. Lots of scams”. In his case: a con artist tricking his group out of their passports then pulling a gun on them. Not an ideal start.

There were plenty of stories like this and on the surface the chaos of the crossing lived up to the hype.

All manner of overloaded contraptions were making their way to the border market over on the Thai side (where apparently the cream of international aid donations to Cambodia are sold off)

We all changed sides of the roads – though without warning or signs.

Use of the horn was frequent and enthusiastic.

And of course the (Cambodian) border guards did their best to extort a little extra ‘tea money’. Luckily no guns involved.

Once clear of the border though, things became more gentle:

I returned a child’s flip flop (dropped from the motorbike in front)

Was waved at by countless school children on big old fashioned bikes

And watched water buffalo wade and young kids splash in the endless flooded rice paddies, of which the main highway gave a pretty good view.

Cambodia was a brand new country for me so I was wide awake taking everything in. From a practical perspective one thing that stood out were the shops. These were often basic with lamentable stock, there were no convenience stores and, in the countryside, not many places to eat. When there were, I was sometimes told the food had ran out and was turned away.

After years of civil war, dictatorship, stifling corruption, and now, dubious Chinese “investment”, there simply isn’t the money to sustain the kind of services I’d taken for granted elsewhere.

This said, there was a strong spirit in the town of Sisophan (my first stop). The market was a bit dusty…

…but the main square was lively with several evening aerobic groups dancing to old cathode TV sets, kids and teens doing laps on roller skates and epic energetic games of sei (a kind Khmer-Vietnamese ‘hackey sack’ but better).

In a strange way I had my own ideas about the Cambodia I wanted to see: deep red dirt roads, bright green paddies and the usual idealised rural scenes from tourist brochures and adventure travel companies. This, surely, was the “real” Cambodia.

I hunted down these ‘red roads’, (all of which were detours), but this was unnecessary. Cambodia was right in front of me on the highway: beautiful, dirty, often fun but sometimes desperate and sad.

On my way to Siem Reap I saw:

– children collecting scrap from the roadside, their eyes bright with excitement as they waved a genuine and heartbreaking ‘hello!’ in chorus.

– hand tractors acting as buses, making bone rattling long distance trips

And countless overloaded mini buses, legs dangling out, motorbikes roped on, and rubbish launched from the windows at regular intervals as they sped by.

There were also plenty of ambitiously loaded bikes.

Every bus, bridge or school I passed bore the badge of some international sponsor: “with the help of USAID”, “From the people of Korea”, further reminders of Cambodia’s struggles.

Roads were flat, but the sun was hot and I rarely took much of a break. The market towns were interesting, but usually uninviting with nowhere to sit. Sometimes the shops stocked so little, I felt bad going in knowing I’d walk out with nothing.

One salvation, from a cycling (and calorie) point of view, were the sugar cane vendors – a refreshing cup of cane juice (served on questionable ice) would set you back around 25 cents.

I pulled over at one of these places around 20km from Siem Reap and, as was often the case, a helpful, English speaking lady appeared from nowhere to assist with the transaction.

We got chatting and she told me there was an English class going on just behind the cane juice stand, “they’d love it if you dropped in”.

It turned out this nice lady was a tour guide in Siem Reap (gateway to the Angkor temples) and had originally arranged an English tutor for her nephews. When other children asked about joining the class, she opened it up to the neighbourhood – 200 showed up to the first session! – “It’s their ticket out of here”, she explained. Eventually they built a classroom and she now puts on free classes five days a week from her own pocket.

When she was younger, she said she’d often be up at 3:00am preparing to walk the 20km into Siem Reap just to find tourists to practice English with. After teaching herself English and becoming a guide, she then learned Spanish (which she can charge more for). She hoped the free classes would make things easier for her nephews and the other village kids.

Of course I’d drop in.

The kids were great, but understandably a little nervous. Really my abrupt entrance was no different to a baguette wielding Parisian appearing in the middle of period 5 French. Sorry guys.

All were on good form by the time I left, though as it was the school holidays, there were actually only 4 students. “Their parents don’t really value education”, the lady explained, “and would prefer them to stay at home and help in the house and the fields.” She said it was a huge problem in the countryside. “As soon as any of them can earn a little money, their parents take them straight out of school.”

I left a donation for some supplies which was reluctantly accepted: “that’s not why I asked you in!”, the lady protested. She said they’d use it to buy a prize for best attendance (a small desk and chair to take home) – “none of them have a place to study”.

I made the last 20km into town dispirited by the hard life faced by so many young people here, but equally blown away by their determination.

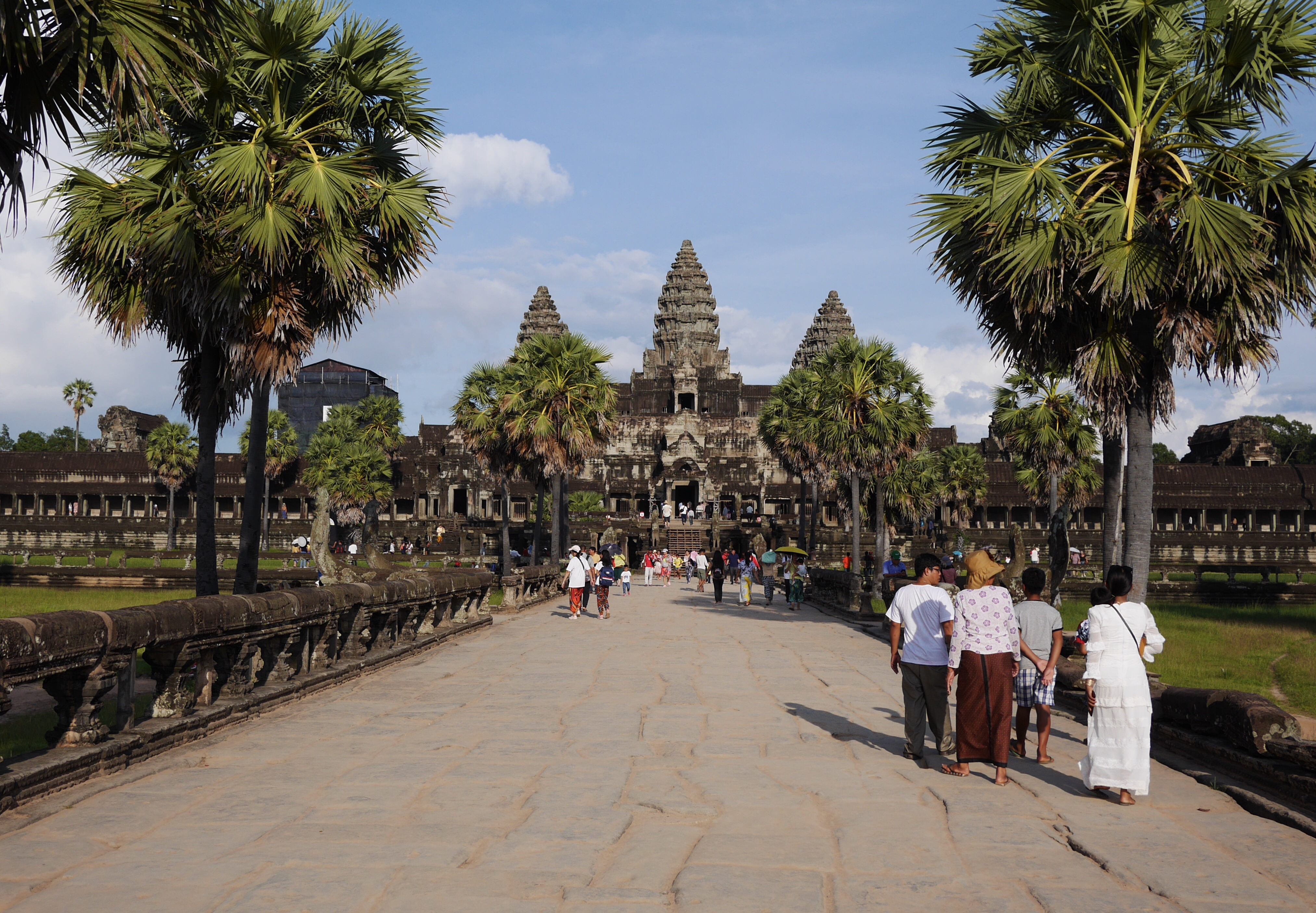

Traffic grew heavier on this last stretch, steeling me up for the bright lights and crowds of Siem Reap, a strange town which acts as a kind of commercial holding pen for the temples of Angkor (one time medieval capital of the sprawling Khmer empire).

In 1300 Angkor was home to around a million people (much more than London and other contemporary world cities), and was the base for a kingdom which stretched over Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. Its power waned though and after repeated invasions the grand capital was eventually abandoned in the early 14th century.

With the Khmer kings out of the way, it’s now occupied by armies of tour groups with colourful umbrellas on constant patrol.

Whilst visitors are promised ‘the mysteries of the Khmer civilisation’, they are likely to find in equal measure: cocktail ‘buckets’, massage parlours and relentlessly optimistic tuk tuk drivers that offer you a lift even when when you are riding a bike.

It’s easy to complain about this (it’s annoying), but the town and temples are a crucial lifeline to the surrounding countryside where with the poorest families earn just $300 USD per year.

Whilst the tourist dollars can help, they also distort the local economy – the temples are full of young children selling postcards, bracelets and posing for photos with tourists – much more profitable than going to school.

The temple authorities have issued a code of conduct trying to encourage better behaviour from visitors. Many are seemingly oblivious to their surroundings though, preoccupied instead with staging clichéd instagram shots and getting maximum value from their selfie sticks.

I almost bought myself a floppy hat and floaty dress so that I could join them, leaning nonchalantly on the ruins and staring into the distance.

In the end, like these guys, I just set off on my bike instead.

I actually had a great day. The complex is massive (I did 50km just going around the main circuit). As expected, the less hyped temples were most enjoyable, though perhaps this was just me getting drawn in to the competitive nonsense of finding the best ‘hidden’ and ‘secret’ spots!

The Angkor area is certainly stunning, but the contrasts are violent; souvenir sellers seem bored and hopeless, visitors sip Starbucks whilst barefoot kids sell ponchos in the rain. It’s a bubble and not precisely as I expected, but as much the “real” Cambodia as anywhere else.

From Siem Reap it was a short ride to Kampong Khleang, a ‘floating village’ on the giant Tonle Sap lake where I’d arranged a homestay for the night.

Whilst on the way I met an interesting man who introduced himself only as ‘White Elephant’. Like everyone over a certain age, he’d lived through the Lon Nol coup, US bombing, Khmer Rouge genocide, Vietnamese invasion and subsequent road to peace and recovery under current strongman Hun Sen.

He was a professor and big in the archaeology scene (speaking French, English and Khmer), but due to the realities of modern Cambodia, he was also a tour guide and told me his shirt had been donated to him by a tourist. He informed me I was taking a crazy route which was totally flooded, pointed me back to the main road and invited me to stay with him next time I’m in Cambodia – “bring your wife!”. He gave me his address which read only: “White Elephant, Siem Reap”.

‘Are you sure this is enough…?’

He looked a little hurt. ‘Everyone knows me! When you get to the airport, just tell them to take you to White Elephant!’.

“OK!”

Back on the main road I stopped for a snack of local sticky rice cooked over coals in bamboo.

After a pipe full of rice you don’t need to eat for a while. This was a shame as I passed more than a kilometre of these vendors lined up wall to wall, maybe even a hundred of them, many stepping out into the road waving the rice sticks frantically at everything that passed in the hope of making a sale. It was quite sad and hard to take as it’s difficult to see there being enough trade to spread around.

Fuelled up on my bittersweet rice, it wasn’t long before I reached Kampong Khleang, a surreal place where all the houses and shops are built on stilts several metres off the ground. In the dry season there is no water at all and people rely on motorbikes to navigate the streets, when the rains come, the water rises several meters and the streets become canals.

To be honest, I was a bit uneasy about visiting this village, it was a bit of weird arrangement and a little voyeuristic. I was essentially there just to ‘look’ at how people lived. It was also extra odd as I couldn’t wander around (without a boat), so just hung out with the family instead.

The guy in charge reassured me a hundred times that spending a night there was the best thing though and much better than arriving on a tour, where much of the money is creamed off by the agency. ‘I buy everything locally’, he said, ‘so when one person stays here, the whole neighbourhood gets business. I’m the only person with a fridge, so people come rushing to me first’. Indeed the ‘streets’ around the house were like an all day floating market, with people paddling around their wares. We bought ice creams from the floating ice cream man and I sat on the deck trying to make my way through ‘First They Killed My Father’, Luong Ung’s tragic memoir of the genocide. Even on a bike I feel I’m travelling far too quickly to keep up with the history of all the places I’m riding through.

I joined the family in their little boat as they ran some errands (quite a funny experience) and chatted again to the owner during a torrential rainstorm in the evening.

He was so fed up with local and national corruption. From his account, nothing gets done without bribes, people with good energy and ideas struggle and give up, whilst others (like those that control the floating village entrance fee), just sit around pocketing cash for themselves.

Another sobering experience and interesting stop, but I was again keen to get moving, feeling I was losing the momentum of my trip with all these breaks.

Luckily Cambodia is almost totally flat, so I could make good progress. Progress is also dependent on food though and sometimes in Cambodia I felt I’d met my match: blow torched cats strung up by their tails, wagons of salted snails and piles of deep fried crickets, it was a far cry from 7-11.

The attitude to personal litter (across Asia) is appalling but in large parts of Cambodia there is no system whatsoever for dealing with household waste either. Some burn it but most just dump everything into a ravine. When the rains come, the rubbish is swept into the river, then into the sea. Problem solved. I cycled by young kids throwing black bags directly off bridges, as routinely as kids might be sent out to put something in the wheelie-bin at home.

Sights like this, and the cats, were depressing but always mixed with non-stop boisterous ‘hellos’ from pretty well every kid I passed and some lovely interactions with local people.

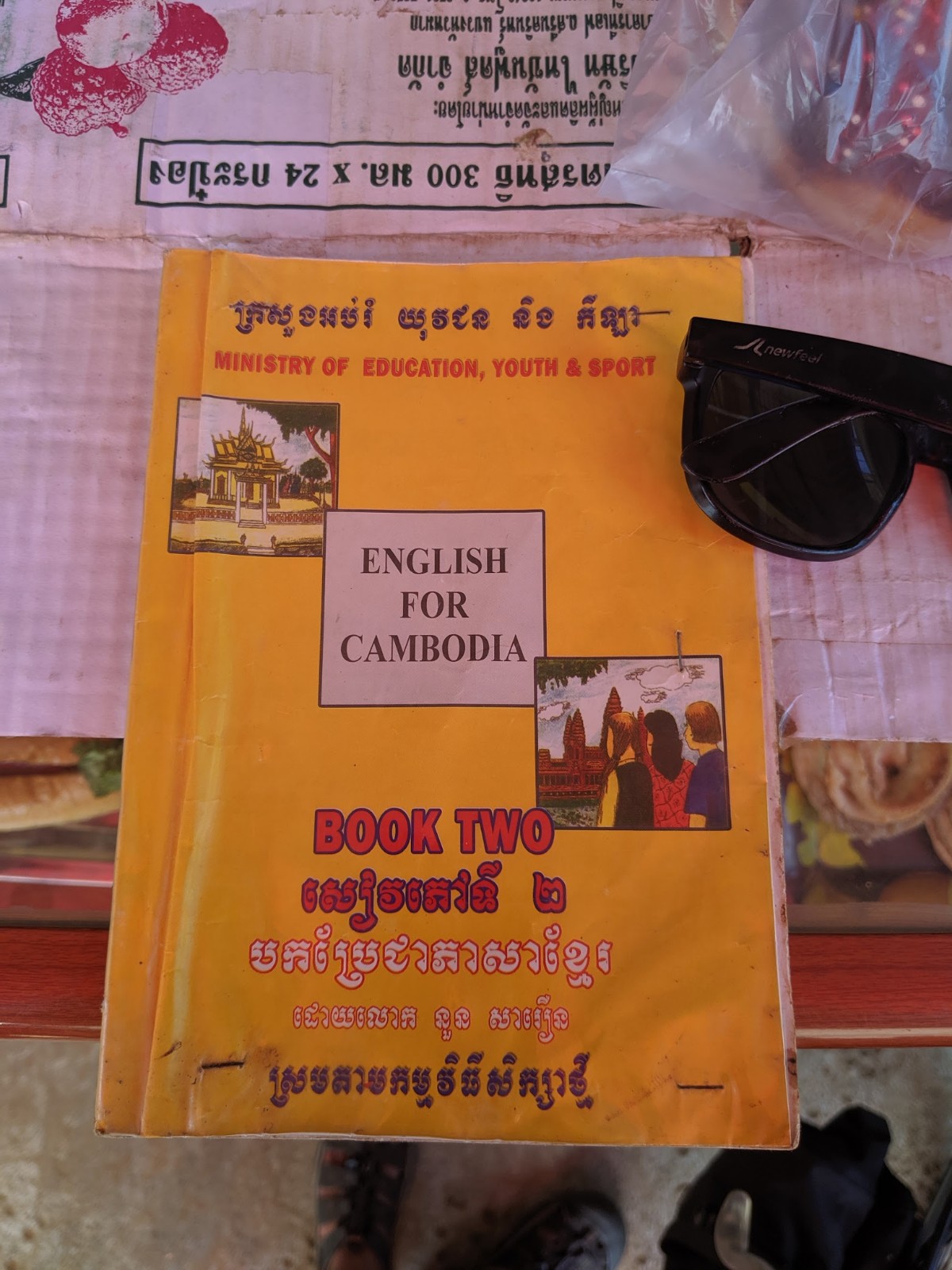

A lady selling homemade donuts (a treat in bigger towns!) was quick to whip out her Ministry of Education English book so that we could have a little chat, at another coffee stop the lady in charge refused to let me leave without filling both my bottles (2.5L) with tea, and when I got lucky, I ate some excellent food as well.

In the right places you are given unlimited rice (they just park the saucepan on the table) and you then take your pick from various simmering pots – which if you’re super lucky, might even have a veg option!

Towards the end of my day cycling on from the floating village, I met my third cyclist of the trip! Ross, from Bournemouth, had actually stayed with Dee (the Warm Showers host in Thailand) the night before I had.

We had lots to talk about and had a good laugh over dinner about the nonsense of riding bikes over long distances in the sun. Ross was riding much faster than me and I didn’t seem to have any trouble keeping up once I set my mind to it. After tearing through the kilometres with him, I decided I could smash the 105 miles to Phnom Penh in one shot the next day.

Ross preferred to break it into two, so I shot off at first light alone.

The miles came easy on the flat and I used the local motorbike ferry to avoid heavy traffic on the way into the capital, sailing in from paddy fields right into the city centre.

Again, I had an idea of the Phnom Penh I wanted to see: steamy and seedy around the edges, but with its own faded-colonial riverside charm

There was some of this.

More than anywhere else though, the city seemed segregated on invisible lines and I felt guilty retreating to the comfort and calm of Western style coffee shops and air conditioned malls which together constituted a kind of “green zone” for expats and local elites.

In my defence, my shopping mall trip was actually to Decathlon to buy some bike gear and to the cinema to watch a Khmer language film.

The film seemed to be a kind of experiment to determine an audience’s threshold to slo-mo car accidents. I think about 5 people died (in slo-mo) in the first 10 minutes alone.

It was a terrible piece of cinema, but the themes resonated with what I’d seen on the ride. The child characters all felt an obligation to care and work for their families, all of which were struggling (partly due to all the slo-mo car accidents, but also due to the effects of unregulated manual labour and lack of health insurance) – the strong moral being that the kids should stay in school. The one kid that did finish his exams somehow had enough to look after everyone else’s parents and, as extra incentive to stay in school, he also had his pick of the girls.

This is an anti-child labour poster from out on the road.

My favourite place in Phnom Penh was without question the waterfront. This, for me, was one of the true mixed spaces where it seemed all were welcome. It was also really fun!

In the space of a few hundred metres I could have had my fortune told, gone for a boat ride, bought a bag of chicken’s feet (or popcorn), given a lotus offering at a shrine or released a cage full of (very sorry looking) little birds. All this before taking on the exercise machines (nowhere has an outdoor gym seen such heavy use, from all ages!), the totally pumping group aerobics or frenetic games of cane ball football in the fading light. I loved it.

I was actually in Phnom Penh a while waiting for my Vietnamese visa to come through. In this time

– I made a visit to the harrowing Tuong Slong Jail – an elite interrogation centre during the genocide

– I then got briefly hijacked by a fake Grab driver

– then fined by the police with a real Grab driver

Perhaps there’s some weird karma in there somewhere.

*Grab = like Uber

Having spent as much time stationary as riding in Cambodia, I was really keen to get moving once the visa came through and put in another big 95 mile day down to the riverside town of Kampot on the south coast.

Though the gradient was no problem, the roads came into their own. What were listed as major transnational routes on Google Maps were in reality rutted, potholed and dusty (check out the roadside butcher by the way).

Route 41 was in a particularly sorry state so I was glad to find an option to branch off and had an enjoyable day in the countryside on a better (apparently minor) road, with hills appearing in the distance for the first time in two weeks!

Hun Sen (the long time authoritarian leader of post-war Cambodia) was a constant companion on these rural roads.

So too was England and Manchester City defender Kyle Walker. I saw several hundred of these boards across Cambodia which adorned even the quietest dirt roads. He (and some team mates) are also pictured on the Cambodian Lager can. I wonder if he knows?

Sadly I had to rejoin Route 41 toward the end of the day, the last stretch of this into Kampot was undoubtedly the worst road I’ve experienced on the trip. Thick clouds of dust took visibility down to 30 or 40 metres at points and I had to stop to put my lights on at 3pm in the afternoon. Trucks and lorries roared by constantly and I felt so bad for the people living on the route, which felt more like living under a volcano, the pictures don’t do it justice as I had to keep my electronics safe!

People seemed to be getting on with it, moving animals, playing football, there was even a car wash, which made about as much sense as an underwater hair dryer.

I arrived caked in dust, looking like I’d been involved in a cartoon explosion.

As with much of Cambodia though, arriving into Kampot I was also arriving into backpacker land.

The guy running the hostel was from Doncaster, so I already felt bad not to be supporting a local business. He made no mention of my grimy appearance and instead made a rehearsed joke about how he was “sorry” but as it was Saturday, it was “happy hour all night!”.

I found these places a bit hard to stomach.

When I came back after getting some food there was a different English guy in a shark fancy dress costume conducting a pub quiz. It was the ‘sex round’- I felt I was back in the Sudents’ Union and couldn’t really grasp why people came all the way to Cambodia to hang out in places like this and eat pulled pork and nachos. Then again, I was one of them (briefly).

I took a day to explore the countryside around Kampot which was very pretty (and a nice escape from the confines of the hostel).

Rick Stein visited Kampot in his SE Asian series (in search of the famous Kampot pepper). Channelling his spirit, I ate perhaps a thousand of these local coconut waffles and as much of this lady’s banana sticky rice as I could handle – delicious!

I then got caught in a mighty rainstorm. I actually hoped to take this little ferry to link up with a circular route on some dirt tracks. By the time I got there though the rain was Biblical.

This lady was crossing with her chicken, so I just got on with it. It was a nice, if intense, ride. My bike was in an awful state by the end (I had to pay to get it pressure washed at a car wash – one of many times in Cambodia, all equally funny). I was soaking and filthy.

In my depleted state I cracked when I got back to the hostel and took them up on a happy hour beer. Sorry. It wasn’t even a Kyle Walker one!

Having hit the coast and seen a little of Kampot, the next day was a short (and extraordinarily bumpy) ride to the Vietnam border.

I had been looking for the “real” Cambodia. In the end I saw all sorts:

– bad tourism / good tourism

– corruption / inspiring people

– environmental carnage

– landmine victims

– wild group aerobics

– fried spiders

– and the looming spectre of Chinese “investment” on the coast**

In its beauty and horror, this was all the “real” Cambodia. Everything was.

**the Chinese development of casinos and hotels in the historic resort of Sihanoukville was considered a national tragedy by all I spoke to